The systems you are part of are unsustainable.

Change is needed.

But your role relates to just one part of system, so how do you lead the way?

You shine a light, with our new guide to system capacity and leadership.

It’s a practical guide for people interested in going beyond system thinking to system doing. It’s for anyone who knows they are part of (and affected by) something bigger than themselves.

Structured in three main sections, it:

- Defines systems, capacity – and the problems you’re having with them!

- Shows you five simple practices for understanding and addressing capacity in the system/s you’re part of.

- Introduces five system leadership behaviours, with principles and practices anyone can follow.

I’ll break down part 3 in a future article. For now, what’s it all about and where do you start?

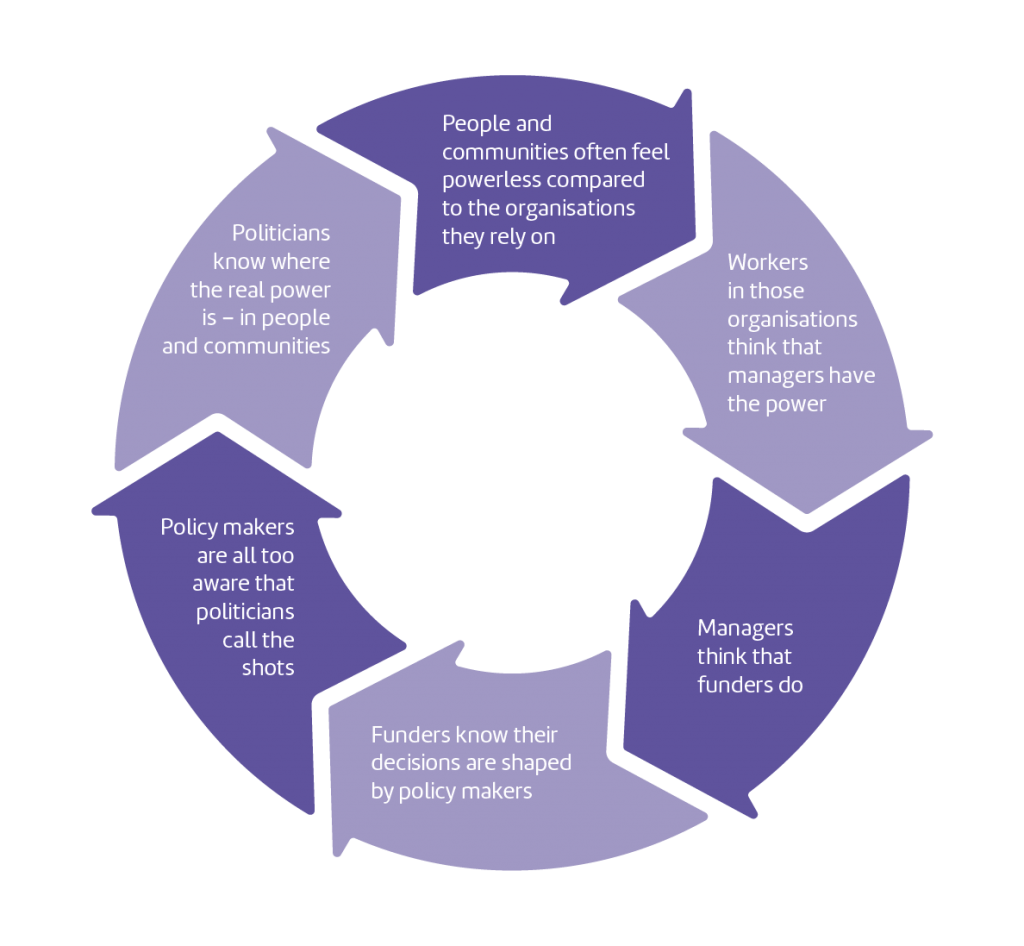

Wherever you work, you’re part of a wider ecosystem. It’s made up of other people, communities, partners, funders and policy makers.

You probably think that things would be better if that system would only change. And whether you work in social care, education, justice, housing, welfare rights or conservation, it’s likely that everyone else in the system agrees with you on that. You’re even likely to agree on what needs to change – other people.

After all, you’re only one small part of a hugely complex environment. What can you do?

Now take a moment to think from the perspective of the other people in your system – wouldn’t they say exactly the same?

Everyone’s influence is limited. But we have choices. One of these is the discipline of taking a step back to see how things fit together. How the strengths, assets and resources in a system can be better used – including your own. How we all have power to shape the system and affect change.

Everyone’s influence is limited. But we have choices. One of these is the discipline of taking a step back to see how things fit together. How the strengths, assets and resources in a system can be better used – including your own. How we all have power to shape the system and affect change.

Five practices for addressing system capacity

1. Assess system capacity

Being able to evidence the amount of capacity within a system is critical for anyone who wants to support it – and influence change.

Before intervening in a system (e.g. by developing a new policy, funding stream or service), monitor its health. Is it ready for new developments? Does it have the capacity and resources to engage with them successfully? The following indicators can help:

Level of resource including:

- Distribution and equity of funding and resource

- Workforce qualifications and knowledge; amount, range and quality of training available

- Levels of staff turnover

Levels of engagement including:

- Levels of activism and the extent to which priorities are determined by those most affected

- Levels of un/met need; diversity of people or communities being reached

- Levels of use of information, services and supports

Extent of coordination including:

- Number, diversity and range of supports (organisations, services, choices)

- Number and nature of joined up responses (networks, alliances, practice sharing)

- Responsiveness of feedback loops e.g. time lag between strategy and implementation; how long it takes for evidence, practice and policy to influence one another. [see 4. below]

2. Tell the truth about capacity – shine a light

Know the true picture. Having information on the indicators above will help you shine a light on system capacity and spotlight challenges, bottlenecks and resources.

Know the true picture. Having information on the indicators above will help you shine a light on system capacity and spotlight challenges, bottlenecks and resources.

Remove the mask. The true picture of capacity is often hidden. It may be masked by things like working extra hours; ignoring workload limits; using waiting lists; accepting referrals when already full etc. Or it may be hidden by pretending that things are fine. They’re not.

Name the capacity issue. Years of austerity and real terms funding cuts have inured organisations to doing more for less: taking on funding that doesn’t cover full costs, extending their reach, addressing issues beyond their core purpose. Then the pandemic hit and capacity was pushed beyond all previous limits. Transitioning out of crisis responses requires being honest about capacity.

3. Provide and build capacity

To develop your own capacity, concentrate on building other people’s. For individuals, this means aiming for ‘second order’ outcomes that focus on empowerment and prevention. (Teaching people to fish, as the old saying goes). Second-order outcomes have a multiplier effect, vital for increasing capacity within society and systems, strengthening people’s ability to help themselves – and others.

For organisations, building capacity means sharing your ideas, resources and ownership of an issue. This spreads your message and increases your impact, giving you access to knowledge, expertise and effort that would otherwise be out of your reach – and budget. Sharing ideas and ownership of an issue helps you to ensure the voice of the people or causes you support gets heard. [There’s much more on this in our Guide to Sustaining Impact and Capacity]

4. Create flexibility

This one is mostly about funding systems. Funding should create capacity, not deplete it. This is not always the case. For example, if funding only covers the costs of direct delivery not apparently frivolous luxuries like supervision, training, pensions, quality assurance and collaboration, it creates an unsustainable capacity problem.

To build system capacity, organisations and their funders and commissioners can:

- Work as partners not purchasers and providers

- Focus on learning

- Invest

- Facilitate.

(There’s much more about all these in the guide itself)

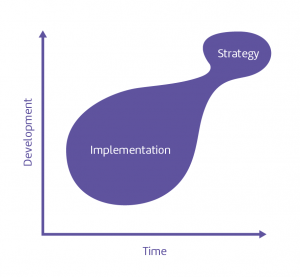

5. Look out for feedback loops and time lags

Aspiring system leaders have to be able to operate in different time zones. It’s like looking through a camera lens: getting the horizon in focus, then refocusing on what’s in front of you, balancing what the system or organisation is doing now with what it might need to do in future. Anticipating what’s coming next and planning long term for a range of different scenarios.

This can create problems of coordination and buy-in. For example, it might mean that colleagues are just getting used to the last change, or the old strategy, by the time the next one comes along.

It’s like when bands want to play their new material, but the crowd wants the familiar songs they can sing along with.

Of course, towards the end of a strategic or policy lifecycle it’s equally likely that practice has caught up with the strategy that was defined 3 or more years ago. Planners need to catch up on practice developments and work out what they mean for the next plan.

If funding, policy and delivery are evidence-based, they can only ever respond to existing evidence. Systems must therefore be designed that either accelerate the availability of data to decision makers, or that put decision making in the hands of people with direct access to the data. This has implications for systems leadership and system change – a topic for next time!

All content © Wren and Greyhound Limited, proudly licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivatives 4.0 International Licence.